SUSTAINABLE SOCIAL LIFE SPACES FOR YOUNG URBAN MIGRANTS

The case of Bengaluru

Background

In a highly globalised world, there is ‘migration’ on a massive scale of not just goods and products—but also crucially of people who move across geographies in search of better opportunities.

The concentration of educational and livelihood opportunities in urban areas has amplified the movement of students, blue and white collar workers within informal and formal economies—a rapidly expanding population in a young country like India, to cities (OECD, 2019).

While the Indian central and state governments have undertaken various initiatives to fill this gap, the majority of social support schemes and policies are directed towards housing ownership for low-income households. As a consequence, high-mobility working professionals, and students’ housing needs have remained largely unaddressed, unregulated and understudied. The needs and challenges of students and working professionals with respect to housing go unrecorded and unaddressed as they continue to maneuver rental housing value chains in isolation.

Rental housing is critical to drive economic mobility, and incentivises white collar migrants and students to move to cities. Our study, conducted between May and September 2020, aimed to understand housing needs and aspirations of such youth populations migrating to Bengaluru, Karnataka.

About the study

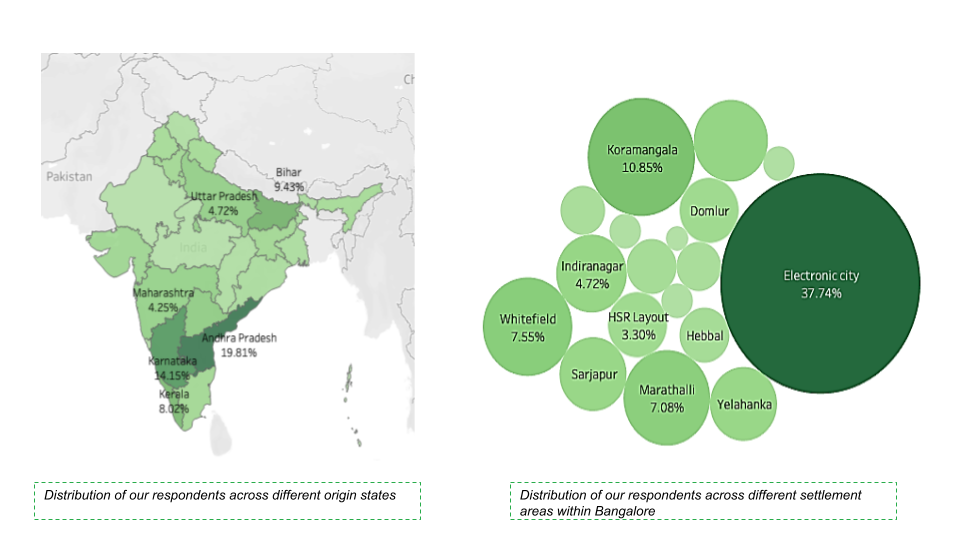

A total of 212 migrants to Bengaluru were surveyed.

Bengaluru is a highly lucrative metropolitan city that attracts this target population by the millions, every year. Here’s brief snapshot on characteristics of survey respondents:

– 35% migrated from other parts of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh and 50% were then concentrated in Koramangala and Electronic City

– Respondents were a mix of students and working professionals

– Respondents were a mix of male and female

This was further supplemented with secondary research to analyse the housing policy landscape.

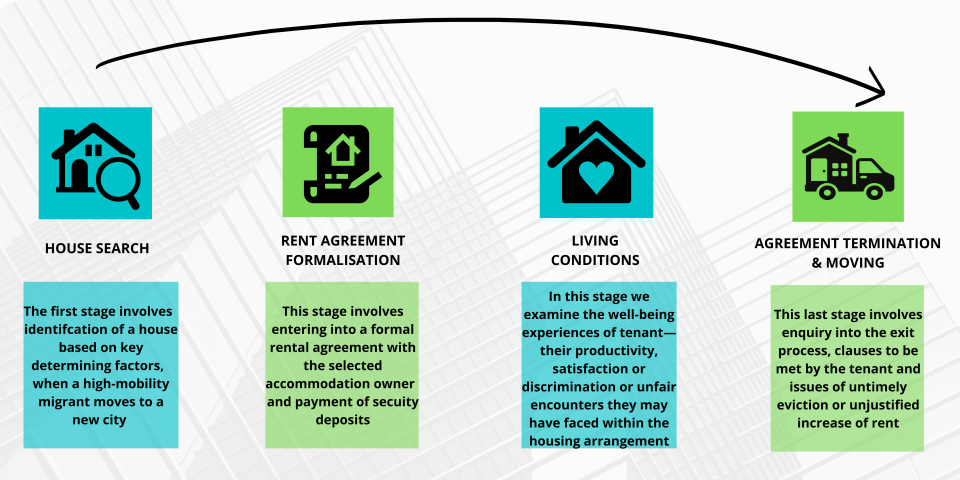

Rental Housing Value Chain

As indicated by research, the target population prefers to live in rented accommodation rather than undergoing processes towards ownership. Therefore, the study explored the housing landscape through the tenant perspective of the housing value chain, as showcased below:

Key insights and challenges across all stages of the Tenant Housing Value Chain

Stage 1 – House Search

– Only 7.84% of total student respondents stayed in university accommodation; of those who had campus accommodation, 50% were pursuing a postgraduate degree, while the other half were pursuing an undergraduate degree.

Stage 2 – Rent Agreement Formalisation

– While 84% people across various accommodations had formal rental agreements, 16% still did not have any formal agreement.

Stage 3 – Living conditions and Maintenance

“Yes, your home has a huge impact on you. For me it’s very important that I live in a good looking place. I want to feel good when I’m home. I can’t live in a dull or congested space. Also, it has to be quiet. This place where I live is right on the main road so you can’t ignore the noise. These small things affect your well-being.”

– Housing had the most impact on academic performance according to students and on mood and personality for working professionals. An astonishing 75% of student respondents staying in university accommodation reported that their housing arrangement is allowing for maximum productivity as opposed to only 38% in other arrangements (Co-living, PG, Private hostel, Rental).

Discrimination

“I experienced judgement and discrimination for being a north Indian. Every night at 10 o’clock our landlord would come to our home and check what we are doing, and even though we wouldn’t be doing anything she would have some or the other complaint for us. We couldn’t even talk freely in our own house; we whispered and yet she had a problem with that bit of noise as well.”

– Students faced more discrimination than working professionals based on food habits, marital status, region or community they belonged. Furthermore, extensive lifestyle-based discrimination was observed in rental flats and PGs while caste/class/community-based discrimination was high for rental flats and minimised in co-living spaces.

– Importantly, there was no caste/class/community based discrimination in university accommodation.

– Discrimination did not vary by gender although it was significantly higher among bachelors as compared to married people.

– 31% reported feeling stereotyped and prejudiced against, based on the fact that they belonged to north Indian states, specifically individuals living in rented flats & PGs.

Stage 4 – Agreement Termination and Moving

“Terminating rental agreements is not flexible at all. If you terminate your rental agreement you can say goodbye to your security deposit. Even if you complete your agreement period landlords still find ways to charge you, basically they want to take away your security deposits.”

Arbitrary increase in rent or untimely eviction

“The last place I stayed at, we did not have a formal rental contract and had a separate maintenance fee which would sometimes vary by month. If there was some capital expenditure the building had to incur then we had to pitch in as well that really made it difficult for us. That’s why students end up in unregulated spaces like PGs where it is cheaper. Now my aspiration is to move to a rented apartment, and it is not affordable at all. The security deposits along with rent is way too high and I think that I’ll never fulfill my aspiration.”

– Students (42%) witnessed highest cases of arbitrary increase in rent or untimely eviction in PGs, followed by rental flats; WPs (48%) witnessed the same in rental flats.

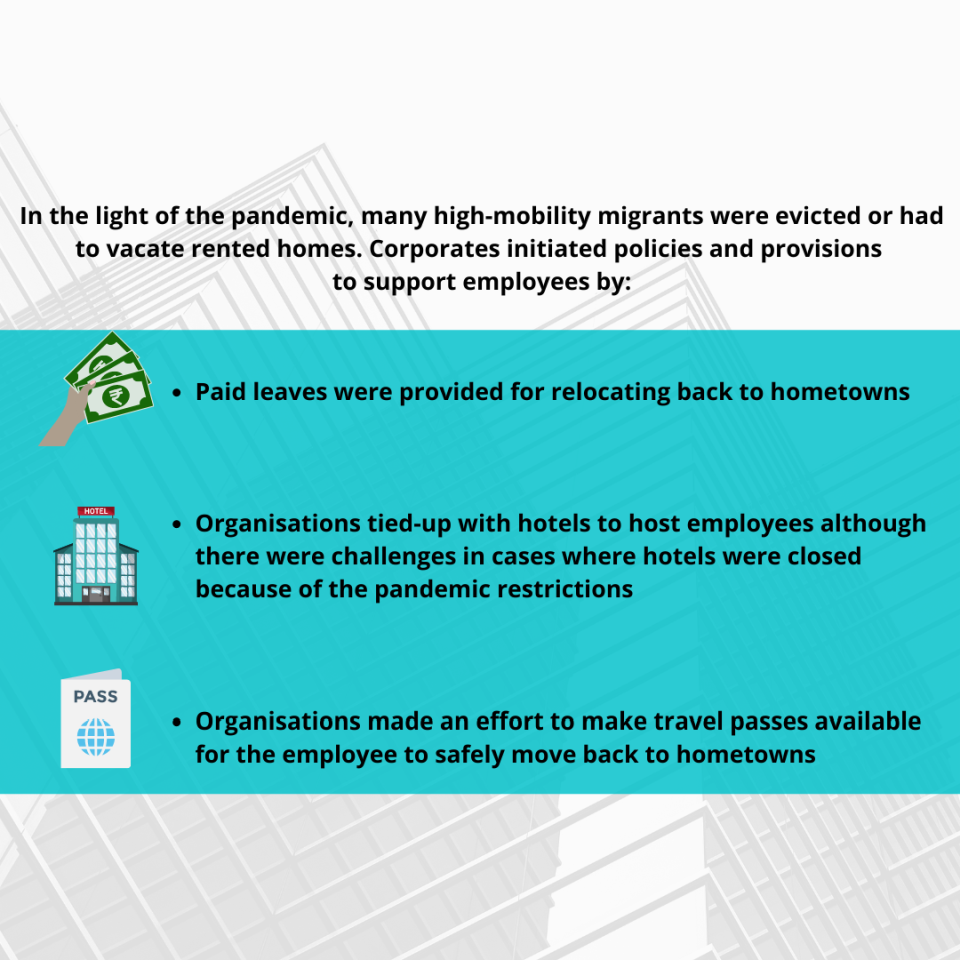

This study inferred that students’ and high-mobility working professionals’ housing needs are deprioritised. Housing arrangements are often not tailored to meet the needs of students, who need an academically conducive environment. Meanwhile, overall holistic care, wellbeing and safety- security measures are absent across the housing policy landscape and housing arrangements. Further, there is no protection or rights given to tenants who encounter untimely eviction or unexplained increase in rent or discrimination during the varied stages of housing value chain.

Key Recommendations to fill the Housing Gap

The identified policy gaps and challenges of the target population through various stages of the housing value chain needs could be addressed by a concerted effort by key stakeholders to affect change in the rental housing ecosystem. The key stakeholders identified with potential to influence change in the rental housing ecosystem would include policymakers and RWAs (Residential Welfare Associations) as well as private sector entities—consortiums of co-living spaces, aggregator models, student bodies, educational institutions and corporates. These stakeholders have the strength and potential to exercise influence to improve the housing situation of this target population.

Emerging Market Disruptors: Co-living and Housing Aggregators can provide potential solutions.

With millennials’ preference for experiential over material commodities, co-living is expected to increase at a strong compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17% during next five years.

India lacks an overarching legal framework covering its entire housing landscape. Housing policies here have historically focused on the ownership model, and on economically weaker and low-income group segments (OECD, 2019).

For a detailed policy gap analysis and in-depth insights from this study, click below.

To save a copy, you can click on the ‘Download’ link on the right side of this page.

————————————-

Notes:

High Mobility Migrants: As per the Deloitte Global Millennial Survey 2018, on an average the maximum tenure of millennials in a job is three years. The survey found that millennials prefer to travel across cities for work instead of investing in a house for permanent stay. Thus, termed as high-mobility migrants.

Working professionals : A working professional, for the purpose of this report, is defined as someone who is engaged in a full time or part time job with an employee or organisation. In the context of this blog, working professionals or professionals typically mean working professional migrants.

Rental housing value chain: The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) defines Rental Housing as a property occupied by someone other than the owner, for which the tenant pays a periodic mutually agreed rent to the owner. The rental housing value chains therefore implies the full chain of activities involved towards the creation of the rental housing market.

————————————-

Sattva has been working with various non-profits and social organisations as well as corporate clients to help them define their social impact goals. Our focus is to solve critical problems and find scalable solutions. We assist organisations in formulating their long-term social impact strategy by strategically aligning with business to provide meaningful solutions to social issues.

We’d love to hear your thoughts and feedback on this topic. Do write to us: impact@sattva.co.in