Female Work and Labour Force Participation in India – a Meta Study

Background

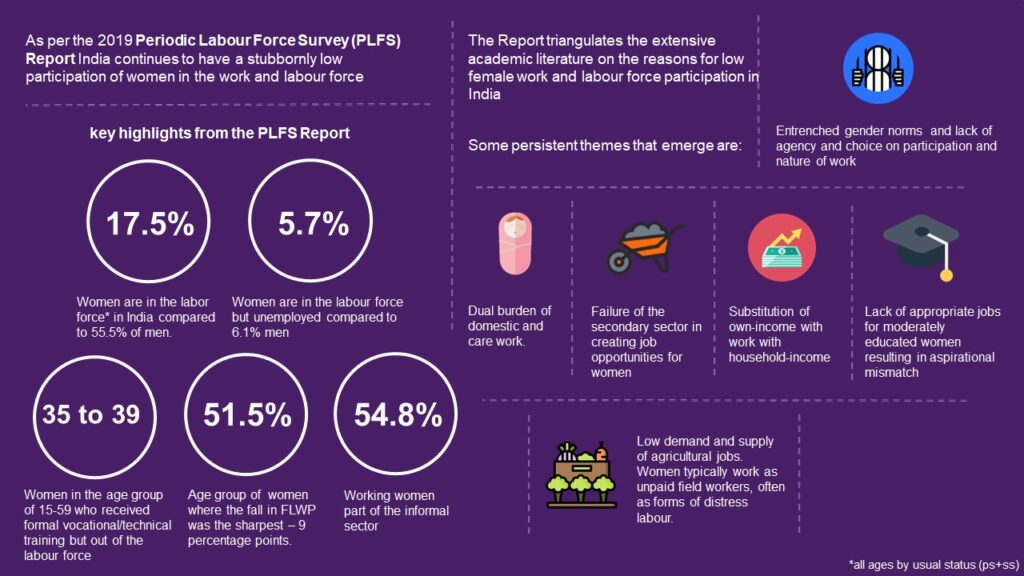

The Indian government has actively pursued labour market policies to increase the female Labour/Workforce participation rate (LWFPR) in India for several decades. The policy-based approach has evolved from educational scholarships, reservations/quotas, to self-employment through self-help groups, and more recently to capacity building through skill training programmes. Challenges in effective implementation coupled with deep-rooted social norms have constrained the impact of these policies on female LWFPR which continues to dwindle. There have been numerous research projects and writings in the academic and public domain analysing the various factors affecting female labour-force participation in India. However, there has been little by way of meta studies to take stock of these public programmes, data, and research across disciplines to motivate further policy development.

This study undertakes a meta-analysis by methodically and comprehensively scanning, documenting and analysing datasets and national policies as well as theoretical and empirical literature surrounding female workforce participation relevant to the national context. In total 13 national level databases, 58 research papers and 53 national level policies were reviewed, documented and analysed to derive policy implications.

Key Insights

1. Basic quantitative labour market indicators are well measured in existing datasets, but indicators related to the quality of the labour market such as terms of employment, job search methods and so on, are rarely documented. Metrics related to gender inclusion and workplace conditions such as access to transport, toilets, childcare and others are equally rare. Another important aspect missing from national databases are behavioural and perception-based data such as career aspirations and expectations from course/job.

2. There is an increasing trade-off between education and employment choices today. The trade-off is primarily driven by a lack of employment for the moderately educated and by non-alignment of job opportunities with the aspirations of women. This is coupled with weak secondary sector performance in job creation for women, and challenges in migration for work for women.

3. Across the landscape of empirical literature, the efficacy of the self-help group (SHG) movement and peer effects have been duly highlighted for their potential to further the cause of women empowerment. Productive asset transfer and ownership has also been documented to have a positive impact of women’s economic participation. Vocational training has been noticed to improve women’s non-cognitive abilities, agency and bargaining power.

4. Competing outcomes of the household and labour market have resulted in women forgoing their employment. Further, deep-rooted social norms, lack of agency and gendering of occupations often leads to women having little choice in their employment and work decisions including care and domestic work.

5. While several policies exist to enable financial support, training, placements and other quantifiable outcomes, few national polices focus on providing support services, such as lodging, safe and convenient travel, migration support and childcare, that enable women to access skilling programmes or be part of the workforce. Budgetary focus on such programmes is comparatively low.

6. Studies are favourable towards the potential of gender quotas and reservations while discussing the need to prevent tokenism and enable inclusion actively through policy design. Of the total policies analysed, 35 percent of the schemes seek to achieve inclusion by setting targets on the total beneficiary composition, 18 percent by ear-marking funds, and 29 percent by “encouraging” inclusiveness as a policy mandate, but without actively designing policy components to bring about change. While 56 percent of the policies analysed are exclusive to women, these policies do not dive further to identify more disadvantaged groups of women.

The full report can be accessed below.

Female Work and Labour Force Participation in India – a Meta Study

Would you like to partner with us to further the conversation around inclusive labour market indicators and policiest? Write in to solutions@sattva.co.in.