Over the last two months, I have had the opportunity to meet and talk to a wide range of people and organisations focused on education. From corporate leaders, innovative social organisations, for-profit enterprises, experts, enthusiasts, schools, school children to policy makers – the sheer size of the ecosystem that is working on the topic, espousing interesting perspectives and implementing innovative solutions on the ground is impressive. And with the recent CSR focus, this tribe is only growing.

It is clear that we have made tremendous strides on the issue of education. However far one travels and however remote, education is aspirational today. Parents want to put children in good schools and want to spend any additional income they get on their child’s education (I met someone who sold his house so that he could send his children to private school). There are schools everywhere and wherever one goes, one is met with the sight of children in uniform walking to school. Organisations have built creative products to impart learning that have gone beyond the Poor-solutions-to-poor-people syndrome (A good test of this is whether I would want my son to use a particular solution. Skill development. No. Sanitation. No. Education. Oh yes.)

But the problem is far from solved – Learning quality is abysmal as ASER continues to remind us. I have personally watched children of III and IV grade struggle with the alphabet in their vernacular language. While the physical infrastructure for education has become ubiquitous, the soft infrastructure and resources haven’t kept pace resulting in poor quality of teachers. While private schools have mushroomed thanks to parents’ willingness to pay, there’s no discernible difference in quality. While enrolment numbers have peaked, attendance continues to be a challenge clearly reflecting poor engagement.

It should be acknowledged that problem of education quality is a harder problem to solve than getting parents to sending a child to school. While getting one’s child enrolled is a black-or-white decision, quality (much like beauty) is in the eyes of the beholder. However, there is no point in having come this far if the children in schools are not learning anything.

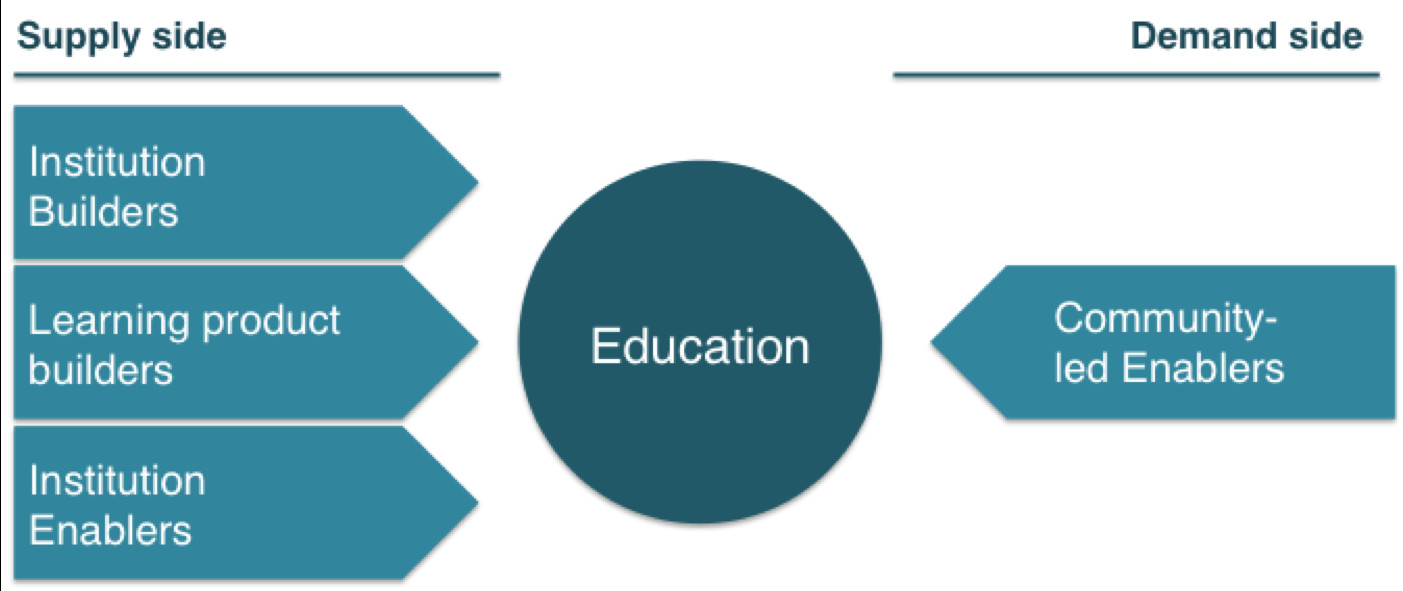

So what is the solution? As I was navigating through the ecosystem, I categorised the education-focused organisations I met into four categories*

Institution builders: Organisations (including corporate foundations and leading NGOs) that are building schools today to address the issue of education – These institutions serve as model schools that are used as grounds to pilot, test and prove models. The learning from these model schools are subsequently shared with other schools.

Learning product creators: Organisations that are creating product-based solutions to address specific learning problems. The products could be technology-based, hands-on kits or a replicable methodology of intervention. These products are delivered through schools or as after-school / out of school programmes.

Institution Enablers: Organisations that see education as an institutional problem and are looking to build the capacity of the school. These organisations focus on building the capacity of the teachers, the school administration, create institution-level intervention programmes.

Community-led Enablers: Organisations that work strongly with the community to strengthen the demand side in terms of awareness, engagement and action. Most of these organisations started with the community as the unit of engagement and realised the value of education.

Of all the groups, the learning product creators vastly outnumber everyone else. Across non-profit organisations and for-profit organisations, there is a strong focus today in creating products that are able to achieve scale, improve a measurable indicator in the short- to mid-term. Each of these products and solutions reach thousands and lakhs of students, receive strong grant and equity funding support and target parents who are increasingly willing to pay for good quality.

The institution enablers are a growing tribe – Leading foundations like Azim Premji Foundation, Kaivalya Education Foundation (and initiatives like TFI, Gandhi Fellowship) are building strong models of intervention to strengthen educational institutions by working on the teachers, the head-mistresses and the overall administration. Organisations like Varthana offer loans to improve the quality of the institution.

The least number of organisations that I met (and this is by no means representative) are organisations that worked with the communities on education. These are, understandably, long-burn initiatives and are not immediately scalable. And unlike product and school-based programs, the contours of such initiatives are not as well defined.

But when one goes back to the question of quality, and if we ask ourselves what is the most important lever to improve quality, the answer is obvious: Education is a market-driven problem today and the institutions will offer what its customers (parents) will value. Unfortunately, the first generation parents who are sending their children to school are unable to engage with the institution on matters of quality of education. So, if parents view school buses, uniforms and english rhymes as the measure of quality, schools will ensure they are addressed and projected. For quality education to become a reality, it is critical for the community to know what quality stands for and make it measurable. Once that problem is solved, institutions will adapt automatically.

During a recent discussion on building assessment tools for schools to improve their performance, I emphasised that the most important version of the assessment tool should be in the hands of the parents and it should be something they can administer and understand. And given the sheer size of the ecosystem that is investing in education today, it is not a problem that is unsolvable.

Which is not to say, supply side initiatives focusing on products and institutions are not important. While the tools are the right ones, they should address a demand that rises towards quality education for it to be effective than create interventions that are pushed to a market where it is not valued.

And this is a matter of the greatest urgency. When this generation of parents, having sold their homes and pledged their future to send their children to schools, realise that the children are neither employable nor educated, it will take us a whole lot more effort to convince the next generation of parents to send their children to schools.

* A thought that was inspired by a conversation I had with someone where they mentioned how everyone sees education as a product problem.