Things have changed for Aakash Sethi in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

He is the CEO of non-profit Quest Alliance, which uses technology tools to improve the quality of primary and secondary education in India. The organisation is present in over 4,000 schools across states including Karnataka, Odisha, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, has worked with more than 70,000 educators and reached close to 2 million learners over the past 15 years. The annual organisational budget is about Rs 60 crore, about 80 percent of which is received through corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds.

Over the past two years, however, there has been a 20-25 percent reduction in funding, Sethi says, because companies have increasingly started diversifying their CSR strategy. For NGOs like Quest, he adds, a cut in funding often translates into serious impact on-ground. This could mean “taking some blows” like having to stop ongoing programmes in schools, phasing out projects that might affect their quality, or even invest their own funds to keep things going and make sure they do not lose the trust and relationship they’ve built with teachers and schools on the ground.

CSR data put out by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) indicates that outlay towards education, which has traditionally been the most-funded social cause for corporates, has been declining for the past two financial years.

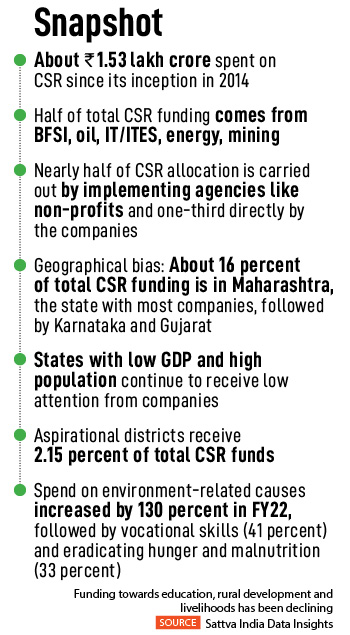

While it remains the top-most cause, followed by health care, the CSR outlay toward education fell from Rs 7,450 crore in FY20 to Rs 6,683 crore in FY21 and Rs 6,351 crore in FY22, says a new report by Sattva Consulting, a social enterprise working with non-profits and corporates to implement CSR projects. On the other hand, outlays towards environment increased by 130 percent in FY22, says the report, which uses the most recent numbers put out by the MCA as of August 2023.

These changes, which indicate an ongoing shift in CSR strategies, could be for a couple of reasons, explains Veda Kulkarni, head of India Data Insights at Sattva who led the development of the report, which is called ‘The State of CSR in India’. First, the dip in education outlays could be a lingering impact of the pandemic, where school closures might have led to companies spending money reserved for education-related causes like school construction, books etc elsewhere.

“We don’t know if the downward trend will continue into the current financial year as well,” she says. The upward trend in environment, on the other hand, could be because of more companies taking up environment and sustainability causes, as a result of both awareness and policy push. “With the mandate of Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report [BRSR] report coming in, more companies are going to look for environment-related channels for CSR funding going forward,” she says.

Sethi says that while it’s understandable that companies will shift their strategies with changing times, they need to make sure that they do not view CSR as simply a compliance requirement and think about the on-ground consequences in the lives of underprivileged people if they decide to pull out of or reduce funding towards projects. According to him, the essence of the CSR law—which requires companies to spend 2 percent of their net profits towards social development and impact—is diluted because some companies lead with a mindset of compliance and short-term output versus a long-term impact. “Development work needs patient investment with the idea of learning from the field and adapting the work accordingly,” he says, adding that companies should adopt a long-term view of the impact they can create with the social projects they decide to back, and commit accordingly.

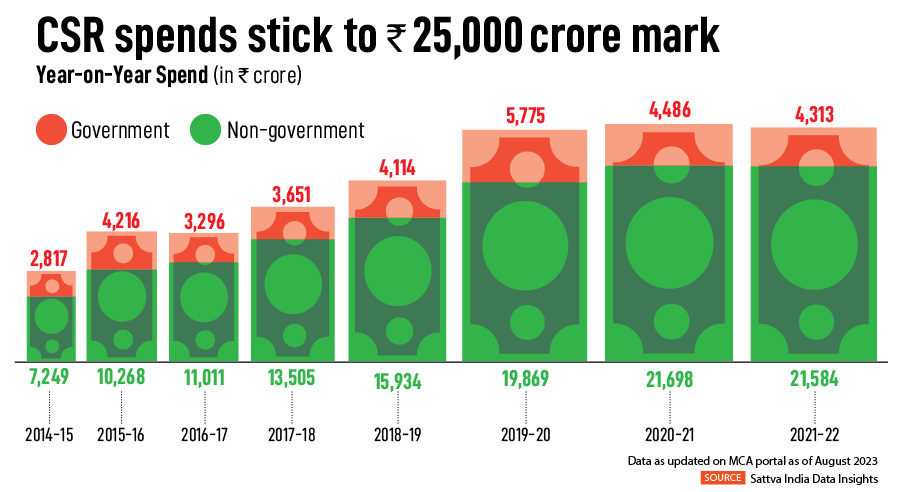

A newsletter dated June 2023 by the MCA agreed that while companies infuse capital into the social sector, they need to make sure they have a more holistic, long-term view. “In FY2021, the CSR spent was Rs 26,210 crore, which is almost twice in comparison to FY2016, where Rs 14,542 crore were spent, which indicates an upward trend in CSR expenditure. However, the impact of CSR funds were not widely felt and there is a need to enhance visibility and impact of these invested funds,” the newsletter says. “To ensure that the impact of CSR is deeply felt, it is imperative that the companies take a long-term comprehensive approach to yield productive results.”

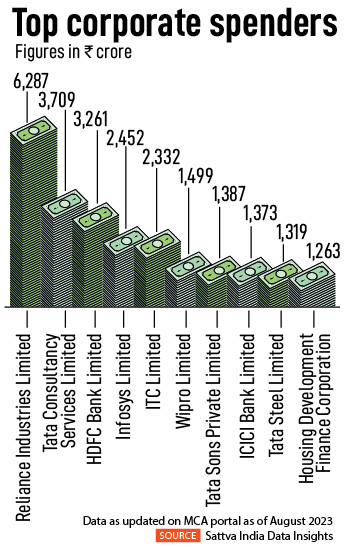

Sattva’s report indicates that the annual CSR spends have more or less remained stagnant at the Rs 25,000-odd crore mark over the past three years, including FY22. From the time it became a law in 2014, companies have spent close to Rs 1.54 lakh crore on CSR till date. The report also shows that companies also continue to have a geographical bias in their allocation. Between 2014 and 2022, Maharashtra, which has the highest corporate presence in the country, received about 16 percent of the total CSR outlays. This was followed by Karnataka at 6 percent and Gujarat at 5 percent. States including Manipur, Nagaland, Ladakh, Mizoram and Tripura received less than 1 percent of CSR funds. These states have low per capita GDP, high scores on multi-dimensional poverty index and low scores on Niti Aayog’s sustainable development goals (SDG) index, but see very low CSR investments every year.

The report also shows that companies also continue to have a geographical bias in their allocation. Between 2014 and 2022, Maharashtra, which has the highest corporate presence in the country, received about 16 percent of the total CSR outlays. This was followed by Karnataka at 6 percent and Gujarat at 5 percent. States including Manipur, Nagaland, Ladakh, Mizoram and Tripura received less than 1 percent of CSR funds. These states have low per capita GDP, high scores on multi-dimensional poverty index and low scores on Niti Aayog’s sustainable development goals (SDG) index, but see very low CSR investments every year.

A potential reason for this could be the way in which companies are interpreting the law, which states that companies shall give preference to the local area and areas around which it operates. “However, it is not mandatory to do so as the world has become too intricately close with the advent of digitalisation and it is difficult to define what the local areas of operations are,” says the MCA newsletter.

As they move beyond traditional geographical constraints, companies should also pass on that flexibility they enjoy under the law to NGOs, and corporate donors need to consider long-term commitments of three-five years based on priorities on the ground, says Neera Nundy, co-founder of Dasra, an organisation that works in the philanthropy and social impact space.

She adds that while lack of readily available organised data, knowledge of causes and organisation due diligence pose as a barrier to effective deployment of CSR funds, companies should start looking at CSR “in tandem with overall corporate objectives as a key enabler to boost their impact”.

Other regulatory restrictions around CSR budgets, timelines and reporting requirements also lead to companies holding on to a compliance mindset. “CSR is all about profits and investments. The budget is getting determined on an annual basis, so how do you take a 10-year view?” asks Srikrishna Murthy, CEO, Sattva Consulting. “One can always flip that question and ask, how many NGOs have a five-or-ten-year plan? You’ll mostly find super-low numbers.”

He agrees that while a one-year view is dangerous, he is seeing more companies adopt a three-five year horizon for CSR allocations, which he feels “should be appreciated”. According to Murthy, companies have been realigning their strategies to meet evolving needs like climate, and are taking on fewer long-term projects than multiple short-term ones, which could explain the dip in allocation levels that sectors like education, livelihoods and rural development are seeing. “As companies get into a more problem-solving approach, they cannot be too spread out. They have to get more focussed. This means they have to choose something, and let go of something else that is critical.”

Sapna Bhawnani, vice president of communications and CSR for the Asia-Pacific region of Alstom, a company that builds urban and freight mobility solutions, agrees that over the past two-odd years, she has gone from having a short-term charitable view of programs the company runs for communities around its factories, to more strategic impact framework that they can stick to for three-five years.

“In rural communities, any kind of change you want to bring out, be it in health care, skilling or menstrual hygiene, you cannot do it in just one year and leave, because at the core of it, you are trying to create behavioural change. With a three-five year horizon, even if you move out of a certain programme or region after five years, you would have managed to create a longer-lasting change.” The company’s CSR allocation is in three buckets: About 40 percent of it is towards grants to support social innovation in sustainable mobility solutions, particularly to make last-mile connectivity more accessible to people; about 50-55 percent of the funding goes to the welfare of local communities located around their six factories; 10 percent is a contingency fund for emergency relief measures.

The company’s CSR allocation is in three buckets: About 40 percent of it is towards grants to support social innovation in sustainable mobility solutions, particularly to make last-mile connectivity more accessible to people; about 50-55 percent of the funding goes to the welfare of local communities located around their six factories; 10 percent is a contingency fund for emergency relief measures.

Nundy of Dasra expects the CSR segment to grow both in absolute terms and in its share of total private social sector funding in India. “Reasons for this projected trend include the expected rise in the Indian economy and India Inc’s profits, a shift from an informal to a formal economy, an increase in the number of companies falling in the CSR orbit, and an increase in the number of companies spending more than the 2 percent mandate,” she says, over email.

The Sattva report shows that in FY22, close to 56 percent companies spent more than their prescribed 2 percent amount, while close to 38 percent companies have less than prescribed or zero spends. About 6 percent companies have allocated exactly 2 percent funds. Murthy of Sattva believes that corporate involvement in the social sector has often been too top-down. “All of us can solve any problem on a PPT, but only once you go to a village or a community do you know what works and what doesn’t work. So understanding of grassroots with a bottom-up approach is very important,” he says.

—–

This article was originally published in Forbes India.

(Picture courtesy: Forbes India)